How to Make Remote Work Better: 5 Tips

Disclaimer: I’ve been working remotely for almost five years, I’m biased, and I think remote work is the future of work. This post was also written before the Covid-19 pandemic. While some things have changed, the principles outlined in this post have remained constant.

For some, the idea of working remotely is equivalent to laying around, watching Netflix (while working of course), and happy hour at 3 pm. For others, they can’t imagine driving into the office, being constantly interrupted, and leaving at the end of the day without a sense of accomplishment.

What causes this major difference in opinion?

If you’re trying to unpack this issue, you may start by looking at the following variables:

- Where do they work? Does the culture support remote work?

- What do they do for work?

- Does the job require constant interaction?

- How big is the company?

I’ve worked at remote-friendly companies with less than 10 employees and more than 150. I’ve seen smaller companies struggle with remote work and larger ones be very successful at it.

For a long time, I looked at the list of variables above and thought the most obvious limiting factor was the company culture.

I still think this is partially true, however, there’s a major variable that flies under the radar. In fact, this reason may be one of the biggest contributors to why remote work isn’t more widespread amongst other challenges.

Yes, I get it. Remote work continues to rise in popularity, but I would argue it is not as prevalent as it should be, especially in the tech industry that prides itself on hiring a diverse workplace (but will only hire people who live within a 25-minute radius of the office).

There are ways for remote work to be better. But before diving in, I need to lay out a few examples first before diving into the main point.

Remote Work Problem #1: The remote-friendly company, but only for a few

I will periodically look at job boards and see that a company is hiring engineers (the positions are remote-friendly), but all the other jobs are onsite. Weird. Why?

Typically this happens because of the following reasons (at least these are the ones I hear frequently):

- The engineering team has a preference to work remotely

- The company can’t hire enough engineers within a 25-mile radius of the office, so they are forced to look elsewhere for talent.

In this example, a particular team inside the organization is unlike the others. If the company culture is a key contributor to being remote-friendly, how does this happen? How does a team inside an organization (that wants you to be in the office), allow a group of people to work remotely?

I promise I will get to my main point, but I need to give another example to set the stage.

Remote Work Problem #2: "I work from home, but only a little bit"

A recent study indicates that 70% of people work away from the office at least one day per week. I’m super skeptical of this research, but anecdotally, it’s becoming more common to hear people say, “I work from home a couple days per week, but I go to the office for meetings.”

Before the COVID 19 pandemic, I found this answer more prevalent for non-technical people. The boss allows remote work up to a certain point, but they can't cross over into being fully remote. It seems too scary.

Once again, the company culture isn't fully supportive of remote work, but a particular remote team can periodically get away with it.

How can this be? And will it change after the pandemic? Will more companies fully embrace being a remote company?

Remote Work Problem #3: The manager's schedule is holding back remote work

Many people (especially the further you go up the food chain) operate on a manager’s schedule. For those of who who haven’t read Paul Graham’s article, Maker's schedule, Manager's schedule you should read it.

Key parts are outlined below:

“There are two types of schedule, which I’ll call the manager’s schedule and the maker’s schedule. The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour.”

This may give clues into why remote work is so popular for engineering teams?

“Most powerful people are on the manager’s schedule. It’s the schedule of command. But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least.”

“When you’re operating on the maker’s schedule, meetings are a disaster. A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in. Plus you have to remember to go to the meeting. That’s no problem for someone on the manager’s schedule. There’s always something coming on the next hour; the only question is what.”

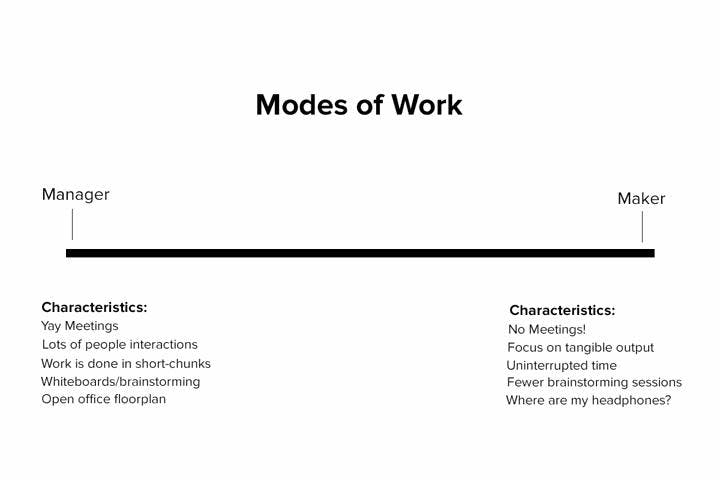

The article lays out two “modes” of work and they exist on a continuum (I made a graphic below to illustrate)

The manager’s schedule thrives on in-person interactions. I’d argue that the key tools in the manager’s schedule toolbox is the power of observation, back and forth interactions, and at its core, extroversion. When the manager’s schedule goes horribly wrong is when activity happens, but there is no meaningful output.

The maker’s schedule thrives when the opposite occurs. It prioritizes output over activity. People-to-people interactions is not as much of a dependency to getting the work done.

If people on the maker’s schedule tend to like remote work and people on the manager’s schedule don’t, how do we break down the barriers?

How To Make Remote Work Better

1. Make remote work more comfortable for the manager's schedule

I fundamentally believe that in order to make remote work more of a reality, we need to address the elephant in the room – people on the manager’s schedule tend to have a lot of leverage inside a company, but they also tend to dislike remote work. How do we get them onboard with remote work so it becomes more a reality for entire organizations? Should we even try?

This may be a tall order, but I think we need to build stuff that takes the best of remote work (like asynchronous communication) and mash it with the stuff that people on the manager’s schedule care about. With that being said, we need to preserve what makes remote work great at the same time.

Put simply, we need to be able to periodically “flex” across the continuum in the graphic above.

For example, I’d argue that Slack is a tool that has made the idea of remote work much more realistic for people on the manager’s schedule. While it’s technically an asynchronous communication tool, it’s also used as an alternative to being in the same room, powering constant back-and-forth communication (which can be annoying).

On the flip-side, remote work has its share of downsides, like the fact that people feel disconnected at times. A common solution to this problem is periodic on-sites, which is an example of “flexing” across the continuum.

If you are a manager, you can do things without meetings, including check-ins and standups. In the next section, we show you how.

2. Create Asynchronous Check-Ins and Status Updates

If you’re a manager and you’re worried about giving up your schedule...what’s next? What can you do to replace it?

Look for other ways to communicate what you usually communicate in a meeting. You can hold many regular meetings--like one-on-ones and daily standups asynchronously.

At Friday, we’re building asynchronous tools (weekly check-in, daily standups, 1-1 meetings, etc) that make the manager’s schedule a bit more asynchronous, but they also help make remote teams feel more connected too.

See our recommended list of remote work software and tools.

Just because you implement these work routines does not mean you have to abandon in-person meetings or video calls.

It's all about finding the balance between these two modes of work and knowing when we need to flex. If we can do this, remote work will be much more common.

In Friday, you can choose the questions that you want feedback on. Or you can run a specialized routine that may occur only weekly or monthly for goal and KPI alignment.

Questions could include:

- What did you do yesterday?

- What will you do today?

- Any blockers?

- What do you need from me?

- Where could we improve?

These answers also provide an account of what people said they would do, their ideas for improvement, and their responses. It’s an ongoing account. Most teams only update this type of information once a quarter or once a year, losing valuable feedback in the process.

3. Understand how and when to communicate

One of the remote work challenges is potentially working too much. That always-on mindset can be alluring for the go-getters, but can quickly lead to burnout without proper checks and balances in place.

To help with this, teams should be clear about how and when they communicate. Think about how the issue can be communicated.

If it’s not urgent, don’t reply or respond in one of your synchronous channels.

For instance, update your project management software or add a comment rather than sending a direct message in Slack when it’s after hours.

Adhering to these clear boundaries in your team communication plan helps keep everyone on track and is a best practice for remote teams. Think about adding a plan to your remote work policy.

4. Think of Remote Work as a High Leverage Activity

In the book High Output Management by Andy Groves, one of his main principles is that productivity will increase with high leverage activities. These are the activities that really move the needle, impact the bottom line, and cause real business growth.

It’s an easy thing to say, but how do you empower your employees to do it? This takes a managerial approach that impacts many employees.

Imagine how a football coach organizes a team. The successful coach isn’t judged by how many total first downs they get or even how many points. It’s based on wins and losses.

If you take that mindset to remote work, you realize it can potentially be a very high leverage activity.

Your employees can:

- Have flexible work schedules, optimizing their time for personal and peak productivity

- Work asynchronously, only responding to the most important request immediately

- Cut down on their number of meetings

As we covered above, managers can use Friday check-ins and routines to see how employees are doing and identify any roadblocks or challenges, truly maximizing their managerial leverage as a facilitator and “coach.”

5. Intentionally Build Your Team Culture

Lots of organizations and teams have stated values, but what about the accidental values?

When building a remote team or even shifting to a remote-first workplace, you’ll bring values and a way of working with you. It takes intentionality to build the team the way you want.

Think about how the team will relate to each other when an office setting is stripped away.

- How will you foster camaraderie in a remote job?

- How will you communicate goals and priorities?

- How will you show appreciation?

A few suggestions:

- Schedule meet-ups in person, such as a team retreat

- Take personality tests to see how the team relates to each other

- Create a space in Slack or Teams for informal conversations

- Keep the feedback loop going

For more on this, check out this article on building relationships in a remote team.

Friday has a lot of tools to help you with this--including icebreaker questions, work routines such as manager or CEO updates, and kudos to thank each other.

Conclusion: Remote Work is a New Paradigm

As we all learned with the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work requires a different approach and way of thinking. There are pros and cons to working in-office and working remotely.

And just as remote employees had to re-adjust their habits, managers must expand their own outlooks and goals, as well. Everything shouldn’t necessarily jump back to “normal” -- that won’t happen again. Instead, managers can be more thoughtful about how their schedules impact remote working and look for ways to mitigate those effects. The tips listed above help create a culture of responsiveness even when working as a distributed team. Need more? Here are even more tips for working remotely.